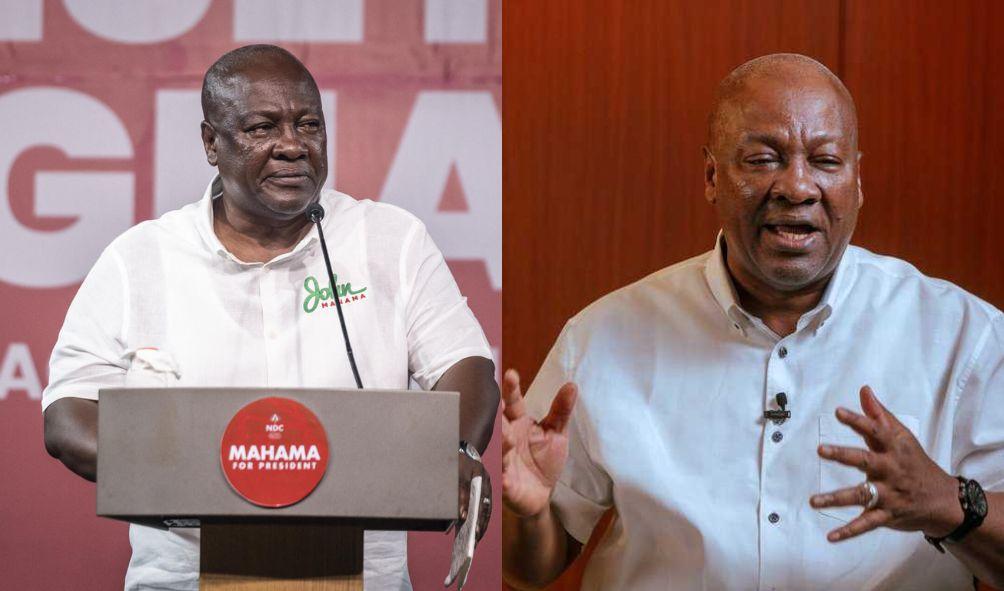

Ghana Joins Record Fifth African Nation with Opposition Win in Elections

Ghana’s Vice-President, Mahamudu Bawumia, has acknowledged his loss in Saturday’s elections, congratulating opposition leader and former President John Mahama on his win. Preliminary results indicate that the New Patriotic Party (NPP), in power since 2016, may face one of its most significant defeats in decades.

Voter dissatisfaction stemmed from rising living costs, prominent scandals, and a severe debt crisis that hindered the government’s ability to fulfill key promises. Consequently, the NPP may have received less than 45% of the presidential vote, marking the first time since 1996 that it has fallen below this threshold.

The recent elections mark the conclusion of a remarkable 12 months in African politics, which have seen five leadership changes—more than ever before. This challenging year has also witnessed opposition victories in Botswana, Mauritius, Senegal, and the self-declared republic of Somaliland.

Beyond these specific outcomes, elections held under relatively democratic conditions across the region this year have largely seen ruling parties lose a substantial number of seats.

This shift is driven by several factors: the economic downturn, increasing public intolerance of corruption, and the rise of well-coordinated and assertive opposition parties.

These trends are expected to persist into 2025, posing challenges for leaders like Malawi’s President Lazarus Chakwera, who faces elections in September.

One of the most notable aspects of 2024’s elections is the number of landslide defeats for governments that once seemed firmly in control—including in countries with no previous history of leadership change.

In Botswana, the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP), which had governed since independence in 1966, was decisively defeated in October’s general elections.

The BDP, which had held 38 of the 69 parliamentary seats, was nearly wiped out, securing only four seats, making it one of the smallest parties in parliament and facing significant challenges in regaining relevance.

ALSO READ:

- Inside Job Exposed: Kenyan Prison Wardens Convicted for Orchestrating Daring Terrorist Escape

- Uganda Pulls the Plug: Nationwide Internet Blackout Ordered Days Before Crucial General Election

- African Elections Under the Spotlight as Zambia Turns to Kenya Ahead of 2026 Vote

- “Two Drug Barons in Cabinet?” Kenya Government Fires Back as Ex-Deputy President Sparks Explosive Drug Claims

- Kenyan Court Freezes Use of Private Lawyers by Government, Sparks Nationwide Legal Storm

In Mauritius, the November elections also resulted in a dramatic loss for the ruling Alliance Lepep coalition, led by Pravind Jugnauth. The coalition received just 27% of the vote, shrinking to only two seats in parliament, while the opposition Alliance du Changement claimed 60 out of 66 seats, leading to a major political shift.

Senegal and the self-declared republic of Somaliland also saw opposition victories.

In Senegal, the political upheaval was striking, though in a different way than in Botswana. Just weeks before the election, opposition leaders Bassirou Diomaye Faye and Ousmane Sonko were imprisoned as President Macky Sall’s government attempted to prevent defeat. After mounting pressure led to their release, Faye won the presidency in the first round, with the government’s candidate securing only 36% of the vote.

Even in countries where the ruling parties retained power, their credibility and control were severely undermined.

South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC) held on to power but saw a decline, falling below 50% of the vote for the first time since the end of apartheid in 1994. This forced President Cyril Ramaphosa to form a coalition government, ceding 12 cabinet positions to other parties, including influential roles such as home affairs.

Namibia’s elections followed a similar pattern. Although the ruling party remained in power, the opposition rejected the results, claiming electoral fraud due to logistical problems and irregularities. Despite these issues, the government recorded its worst-ever performance, losing 12 of its 63 seats and barely maintaining its parliamentary majority.

Across a region traditionally known for its long-standing governments, the past 12 months have been marked by vibrant, competitive multiparty politics.

The only exceptions have been countries where elections were considered neither free nor fair, like Chad and Rwanda, or where governments were accused of rigging or repressing opposition in places like Mozambique.

Three key factors have made this year particularly challenging for those in power.

In Botswana, Mauritius, and Senegal, rising public concern about corruption and power abuse eroded government credibility. Opposition leaders capitalized on this discontent, rallying support by criticizing nepotism, economic mismanagement, and the violation of the rule of law.

In Mauritius and Senegal, the ruling parties further damaged their legitimacy by undermining their supposed commitment to political rights and civil liberties—a critical misstep in countries where democracy is deeply valued.

Economic mismanagement was also a pivotal issue, particularly as high food and fuel prices inflated the cost of living for millions, fueling public frustration.

This economic anger not only contributed to government defeats but also sparked youth-led protests in Kenya, challenging President William Ruto’s government in July and August.

This phenomenon is not confined to Africa. Similar economic discontent influenced the defeat of the UK’s Rishi Sunak and the Conservative Party, as well as the rise of Donald Trump and the Republican Party in the United States.

What stands out in Africa’s power shifts this year is the way opposition parties have adapted and learned from the past.

In some cases, like Mauritius, opposition groups developed new strategies to safeguard the vote by meticulously monitoring every stage of the electoral process. In others, they formed new coalitions to present a unified front to voters.

In Botswana, for example, three opposition parties and several independent candidates united under the Umbrella for Democratic Change, effectively outmaneuvering the BDP.

These strategies are likely to continue to challenge leaders in upcoming elections, such as President Chakwera in Malawi, who is already grappling with public frustration over the economy.

Ghana’s NPP defeat marks the fifth leadership change in Africa within a year. The previous record, set in 2000, was four opposition victories.

The increasing number of electoral defeats, set against a global backdrop of democratic decline and rising authoritarianism, is especially striking.

It suggests that Africa possesses a higher level of democratic resilience than often acknowledged, despite the persistence of authoritarian regimes in some areas.

Civil society groups, opposition parties, and citizens have mobilized in large numbers, demanding accountability and punishing governments that have failed both economically and democratically.

For international governments, organizations, and activists seeking new ways to defend democracy, Africa, often perceived as an inhospitable environment for multiparty politics, offers valuable lessons in democratic recovery.

Ghana Joins Record Fifth African Nation with Opposition Win in Elections